Students brace for 'worst ever year' as dropout rate surges

August 13, 2023Students brace for the ‘worst ever year’ amid tougher grades, strikes and a housing crisis as dropout rate surges

- Nick Hillman, of HEPI, said dropouts mean students’ lives have gone off track

University students are facing one of the worst years in recent history as housing shortages, strikes and the cost of living crisis fuel dropouts, experts warned last night.

A record 32,600 students withdrew from their degree course in the last academic year – 9 per cent more than by the same point in 2021/22, according to data from the Student Loans Company.

The number dropping out is expected to rise next year, with gaps in teaching due to strike action leaving students in a ‘nightmare’.

A high of 2.1 per cent of students had quit their studies by the end of May, up from 1.9 per cent in 2021-22. For some courses the dropout rate was nearly 30 per cent.

Nick Hillman, from the Higher Education Policy Institute think-tank, said: ‘This is one of the worst years, but next year is likely to be worse. Every drop out is a tragedy, it means students’ lives have gone off track – and they still have their debts.’

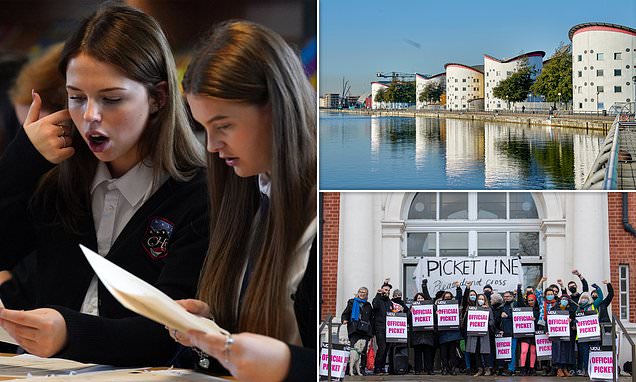

The warnings come ahead of A-level results day on Thursday. With the number of A and A* grades awarded expected to be reduced, competition for places this summer will be tougher (file photo)

The number dropping out is expected to rise next year , with gaps in teaching due to strike action (pictured) leaving students in a ‘nightmare’

He said a shortage of housing is a problem as the number of teenagers enrolling on courses is rapidly outstripping provision, leaving universities unable to guarantee accommodation or forced to place students further away.

Bristol University is putting some students up in Wales, while Exeter University has five applicants for every place at its most popular location.

Mr Hillman said: ‘Demand for higher education is strong, particularly international students who tend to live in that kind of private accommodation. It’s less affordable to build new blocks and private landlords have been taking a lot of properties off the market that they used to rent to students – they might have sold them or rented them privately.’ Soaring rents have also exceeded the 2.8 per cent rise in maintenance loans, leaving students more dependent on the ‘bank of Mum and Dad’, Mr Hillman added.

One mother, whose son spent months trying to find second-year accommodation at the University of Nottingham, said: ‘If we don’t resolve his accommodation, he may have to take a gap year. It’s mad.’

Lee Elliot Major, a professor at the University of Exeter, said: ‘When you look at how much it costs now to be a university student, our student finance system just isn’t capable of covering the costs.’

Prolonged industrial action at universities across the country has also affected students. Mr Hillman said: ‘With university lecturers not being there some of the time, students are getting even less support.’

A shortage of housing is a problem as the number of teenagers enrolling on courses is rapidly outstripping provision, says Mr Hillman (pictured is student housing for University of East London)

More than 120,000 students have joined a legal action by the Student Group Claim to sue their universities for the disruption to teaching caused by strikes and the pandemic.

Yesterday, education minister Robert Halfon urged the University and College Union and the Universities and Colleges Employers Association to reopen talks over pay and end industrial action. He said: ‘It is imperative that higher education providers and staff continue to do all they can to minimise disruption and provide clarity to their students.’

The warnings come ahead of A-level results day on Thursday. With the number of A and A* grades awarded expected to be reduced, competition for places this summer will be tougher. Education Secretary Gillian Keegan told The Sunday Times: ‘During the pandemic, results were higher because of the way grades were assessed – now grades will be lower than 2022 and more similar to 2019.’ Last year’s inflated grades meant some students were accepted on to courses they may otherwise not have qualified for. Some might have struggled to keep up as a result, leading them to drop out.

Ms Keegan added: ‘It is extremely vital that qualifications hold value so that universities and employers understand the distinction between grades when recruiting, and students get the opportunities they deserve.’

Source: Read Full Article