1.5 billion humans share their bodies with worms. But how does one get into a brain?

August 30, 2023Surgeons plucked a live roundworm from a woman’s brain in a hospital in Australia. What was it doing there?

Save articles for later

Add articles to your saved list and come back to them any time.

The woman’s symptoms baffled doctors. When she first arrived at hospital in early 2021 she complained of three straight weeks of abdominal pain and diarrhoea, then a dry cough and night sweats. Her white-blood-cell count was elevated but there was no evidence of infection or autoimmune disease. Doctors diagnosed her with pneumonia and put her on a corticosteroid; her symptoms seemed to improve a little.

A few weeks later, she came back, her fever running hot again. A CT scan revealed lesions in the lung, liver and spleen. Doctors went deeper this time, running more tests, but still couldn’t find the cause; they guessed her immune system may have gone haywire and began treatment.

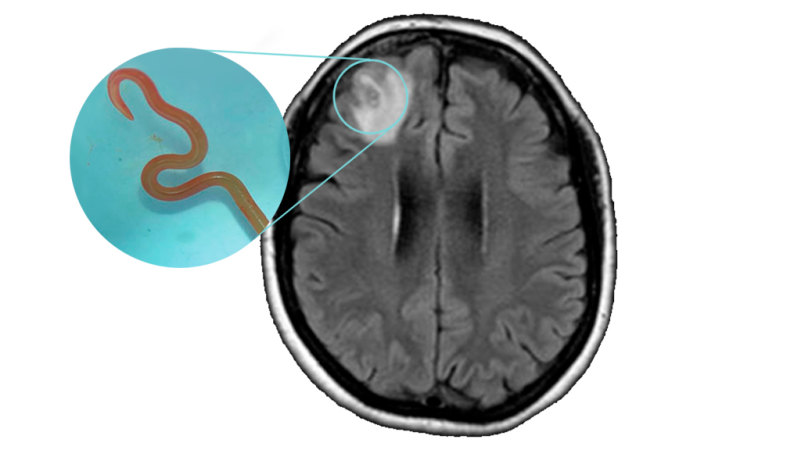

Then, in 2022, the woman suddenly reported forgetfulness and worsening depression. MRI scans showed a pale lesion on the front of her brain. Surgeons went in, not sure what they would find.

Under her scalpel, neurosurgeon Hari Priya Bandi detected a “string-like” lump that, when tugged at, revealed itself to be an eight-centimetre worm, still wriggling. The worm, later identified as Ophidascaris robertsi, has never been seen in humans before, let alone brains. The case is a more-than-one-in-a-million occurrence, say parasitologists.

Yet human infection with worms is extremely common, with dozens of species specially adapted to getting into our guts; perhaps 1.5 billion people worldwide share their bodies with worms.

How does this happen? Is there anything to be done about worms? And how does a roundworm live in a woman’s brain?

An MRI of the patient’s brain revealed a lesion at the front … that turned out to be a worm.Credit: Emerging Infectious Diseases

How did this worm get in there?

It’s not fully clear, but the team of doctors and scientists who pulled the wriggler from the woman’s brain suggest she accidentally ingested a worm egg.

Ophidascaris robertsi, a native Australian worm, is not adapted to live in humans – it lives in the stomachs of Australian carpet pythons, shedding eggs in the snakes’ poo. Small animals such as rats or bandicoots eat the eggs when digging through soil; the worm hatches, penetrates the gut wall into the space around the organs, and sets up home.

The growing worm absorbs nutrients from the host and tries very hard not to be noticed by the immune system. If it can manage that, it can live happily there for years, says Professor Jan Slapeta, one of the parasitologists who was first to examine the brain worm.

“The worm tried to escape, so it probably went through other organs, tried to hide.”

“Imagine you’re in a lounge room with a couch, and all the food you can imagine. You just sit and grow – that’s all the worm does.”

The worm then waits for its host animal to be eaten by a python, at which point it can reproduce. “The circle of life,” says Slapeta.

The worm that ended up in the woman had a far less enjoyable time of it. Ophidascaris robertsi eggs are triggered to hatch by stomach acid; this worm likely broke out and slithered through the gut wall. But rather than find a happy home, the worm soon came under attack from the woman’s immune system. “The worm tried to escape, so it probably went through other organs, tried to hide,” says Slapeta. “And, unfortunately, it found its way to the brain.”

Her symptoms were likely caused by a cat-and-mouse chase as her immune system chased the worm around her body; the scientists suspect worm larvae or juveniles were present in other organs. She was given anti-worming and anti-inflammatory drugs after surgery.

The worm, after it had been removed from the woman’s brain.Credit: Canberra Health Services

How common are worm infections in humans?

Worm infections are rare in humans in Australia but very common in less developed countries, especially in the tropics.

Worm eggs typically germinate in the soil, ready to be picked up by humans and animals. To do so, the soil needs to be warm and moist – meaning most of southern Australia is low risk.

Worms are typically transmitted in human and animal faeces; adult worms living in a person’s stomach pour out thousands of fresh eggs every day, which end up in stool. Australia’s high-quality sanitation systems mean worm infections are uncommon in urban areas, except pinworm, which typically infects children and causes an itchy bottom.

Hookworms can hatch in the soil, and when someone walking barefoot picks up the larvae, they can penetrate the skin. From there, the hookworm can get into the bloodstream and then into the lungs, and then “creeps up your windpipe till you swallow it, and then it stays in your gut”, says Professor Alex Loukas, James Cook University parasitologist.

“If it rains, there will be a washing effect on the faeces, and the worms can disseminate in the area.”

Our biggest worm risk comes from our companion animals: dogs.

One study of the scat at Australian dog parks found more than 44 per cent of parks had at least one species of parasitic worm, mostly hookworms. Dr Vito Colella, parasitologist at the University of Melbourne and one of the study’s co-authors, suspects dog parks may be a key transmission site.

“You don’t need to step on an actual poo. If it rains, there will be a washing effect on the faeces, and the worms can disseminate in the area.”

The worm is known to infect native carpet pythons.Credit: Allieca

In regional Indigenous communities, rates are much higher – up to 60 per cent of people in some communities have Strongyloides stercoralis, a parasitic worm that infects the stomach. For immunocompromised individuals, infection can be fatal.

Loukas has a different perspective. He likens human-adapted worms to the bugs that inhabit our gut microbiome. Worms and humans are “old friends”, he argues, having lived and evolved together for hundreds of thousands of years. “Our bodies have evolved to expect to have them on board. And now, our immune systems are deprived of signals we’ve evolved to expect from worms,” he says.

“All these autoimmune diseases that are exploding, allergies, even things like diabetes – we know worms have various properties that protect against these sort of diseases.”

Can you get this from foraging? How do you avoid getting a brain worm?

The leading theory for the brain worm infection in the woman, who lives in south-eastern New South Wales, was that it happened after she went foraging for warrigal greens, a native plant with a texture similar to spinach.

The odds of a worm egg from a python parasite being on a foraged vegetable, and then the worm surviving inside the body, are extremely low, experts say. “This is one in a million – probably more than a million. Probably, this will never again be repeated. No one needs to worry,” says Slapeta.

Experts offer a few tips for avoiding worm infection. People should regularly de-worm pets, says Colella.

“The other message from this case is about foraging,” says Associate Professor Sanjaya Senanayake, part of the team that studied the worm pulled from the woman’s brain. “People who forage should wash their hands after touching foraged products. Any foraged material used for salads or cooking should also be thoroughly washed.”

Fascinating answers to perplexing questions delivered to your inbox every week. Sign up to get our Explainer newsletter here.

If you'd like some expert background on an issue or a news event, drop us a line at [email protected] or [email protected]. Read more explainers here.

Most Viewed in National

Source: Read Full Article