Charles has done the hard yards. Now he’s more popular than ever

May 6, 2023Save articles for later

Add articles to your saved list and come back to them any time.

London: A slim, fresh-faced Prince Charles landed in Sydney on January 31, 1966 having never before travelled outside Europe.

The 17-year-old, bound for six months of schooling at Geelong Grammar’s Timbertop campus, in the Victorian Alps, flew Qantas and the crew was told to address the heir to the British throne simply as “Prince Charles” rather than the more formal Your Royal Highness.

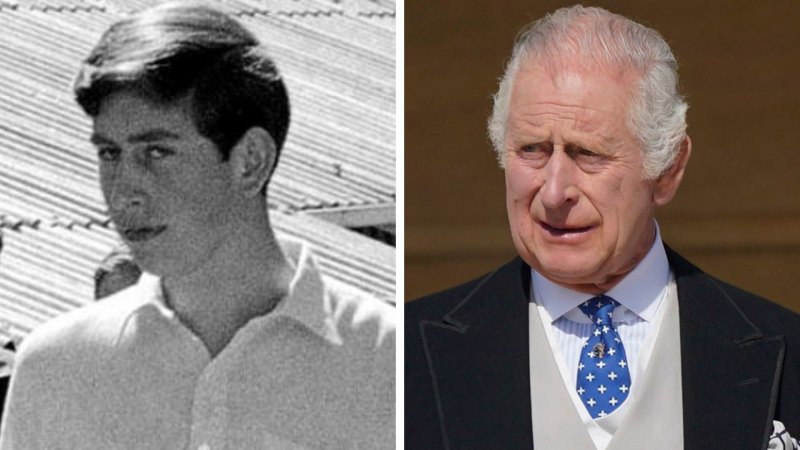

A 17-year-old Charles, right, at Timbertop in Geelong, Victoria, in 1966.Credit: Fairfax Media

It was a grand plan for the young prince to, as newspaper columnist Keith Dunstan wrote at the time, “get to know the Commonwealth and for the Commonwealth to get to know him”.

In Canberra, the governor-general Lord Casey awaited and so did Harold Holt, the prime minister, and their wives. The ceremony was all over in several minutes and the airport crowd was less than 200. There was next to no formality, no speeches, no interviews, just a shake of the hand and straight to Government House where he stayed for a few days.

The next morning Charles managed to get the jump on the waiting press pack and head to a local nature reserve where he met a man and a horse. When the photographers found him after a tip-off he was most pleasant and happy to be photographed.

“How did you fellows get here so quickly?” he said.

The first recorded conversation between the future king and the Australian press.

“That’s a fine horse, Prince Charles,” said the pressman. “Yes,” he replied.

King Charles III is enjoying an unexpected rise in popularity.Credit: Getty Images

King Charles III has often referred to that six months in Australia as “by far the best part” of his education. Most of the future king’s youth was in British boarding schools, but rural Victoria offered a very different type of schooling, where, as Sally Bedell Smith, wrote in The Lonely Heir, he undertook cross-country expeditions in blistering heat, logging 70 miles (112 kilometres) in three days – climbing five peaks along the way– and spending nights freezing in a sleeping bag.

“He encountered leeches, snakes, bull ants, and funnel-web spiders, and joined the other students in chopping and splitting wood, feeding pigs, and cleaning out fly traps.”

They were formative times for a young man whose destiny would appear to torment him for the next six decades. Some of his classmates became friends for life, having been largely more accepting than their English counterparts. They treated him, mostly, like any other boy.

“While I was here I had the Pommy bits bashed off me,” Charles said years later during a return visit to Australia.

He described those hikes “in a blood-stained shirt” as “hell”, he looked back with great affection on his short spell here, saying “it was good for the character”.

At 74, Charles becomes the oldest British monarch to ever be crowned. As Prince of Wales – a title which defined his life for so long – he was restless, driven and capable of summoning up great force in prosecuting his own beliefs on the environment, architecture and farming.

He is no stranger to the corridors of power. He’s met with Australian prime ministers since the 1960s and met every American president since Jimmy Carter.

“Some of us have chosen public life as something I think it’s a very honourable profession,” Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese, in London for Saturday’s historic coronation service, said in an off-the-cuff speech on Thursday evening.

“But for the royal family, they’re born into it. And they serve as their duty.”

Albanese, a devout republican, sees this service and the crowning of a new king as about “the future and going forward”.

“One of the things that I certainly admire about King Charles – and the Prince of Wales [William] who is continuing that tradition – is their concern about the future,” he said. “Their concern and outspoken views about climate change, about the need to protect our planet, about the urban environment, about a whole range of issues, including respect for Indigenous Australians.”

Prince Charles takes a fall at Warwick Farm in 1983 in front of a crowd of 10,000 Australians. He was unhurt and later joked about the incident.Credit: AP

Veteran Evening Standard royal correspondent Robert Jobson says Charles III is a “deep-thinking, spiritual man”. Jobson says he is not only a worthy recipient of the crown, but an anchored monarch who Britain is blessed to have in uncertain times.

“He is not cynical but intuitive, instinctive, and perhaps a little sentimental and overemotional at times,” Jobson says.

“He may have been born into a family with huge wealth and privilege, but he has always tried his best to justify that good fortune by working tirelessly to improve the lot of others less fortunate than himself.”

He says Charles would be the first to admit he is not perfect.

“He can be obsessive, a little eccentric, and he does have a short fuse, but his temper is invariably short-lived,” said Jobson, who has written a new book Our King: Charles III: The Man and the Monarch Revealed.

His younger son, Prince Harry, wrote in his controversial memoir Spare that when his father watched the BBC news on television, he would often end up throwing the remote control at the screen out of frustration.

Charles’ biggest challenge of late has not only appeared to be holding his family together but remaking an institution that has become more and more irrelevant to many of its 14 overseas realms.

A new poll this week found nearly half of the British realms – including Canada and Australia – would vote to become republics if a referendum was held tomorrow. The research by former Conservative deputy chairman Lord Ashcroft, revealed a blunt assessment of the scale of the challenge the monarchy faces abroad.

Of the 14 overseas countries where Charles is head of state, six – Australia, Canada, the Bahamas, Jamaica, the Solomon Islands, and Antigua and Barbuda – would vote to ditch the monarchy.

Nearly all the other eight nations with Charles as head of state – New Zealand, Belize, Grenada, Papua New Guinea, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, and Tuvalu – hang in the balance.

Ashcroft said at first glance, it suggested a division of varying magnitude as to what people think about the royal family, or how they see the institution of the monarchy.

“In fact, it has more to do with how they see themselves, and what, if anything, they think they gain from their relationship with Britain and having the King at the apex of their political system,” he said.

“For republicans, the objection to the Crown is not that it stops them doing what they want but that it feels irrelevant to their country and their allegiance to it seems an anachronism.”

He said that was especially true in Canada and Australia, where people felt the monarchy was incompatible with what they considered their inclusive and egalitarian national character. Elsewhere, the monarchy’s association with the history of slavery and colonialism was another inescapable factor, especially in the Caribbean.

On the eve of his official crowing, Johnny Briceno, the prime minister of Belize, said it was “quite likely” that his nation would be the next to become a republic, while Jamaica said it could hold a referendum on the move as early as next year.

Charles is also facing calls to apologise for Britain’s role in the slave trade, with 12 indigenous leaders demanding that he apologise for centuries of “genocide and colonisation”.

“This country has a new King,” Australian independent Indigenous senator Lidia Thorpe, a signatory to the letter, said.

“Australia must move towards cutting ties with the Crown and becoming a republic, but we have unfinished business to settle before this can happen.”

The backlash from around the former Empire is a reason why Charles is desperate to show at the weekend that he wants to be a monarch for all his subjects, irrespective of their race or religious beliefs.

Hands-on in the planning, it’s been reported he is determined to deliver a coronation fit for the people he serves. He also hopes the long weekend – there’s a coronation concert on Sunday and a charity volunteering drive on Monday – will be both uplifting and historic.

Last month the King hailed the “extraordinary potential” of the Commonwealth and spoke of the “imperative to act” on its ideals to improve the lives of its 2.6 billion people.

Delivered from the great pulpit at Westminster Abbey, Charles recalled his mother’s “particular pride” in Commonwealth Day, and said: “The Commonwealth has been a constant in my own life, and yet its diversity continues to amaze and inspire me”.

He told the 2000-strong congregation of senior royals, politicians and dignitaries: “It’s near boundless potential as a force for good in the world demands our highest ambition; its sheer scale challenges us to unite and be bold”.

In Britain, any doubts over whether the King will be good for the monarchy have faded and his popularity has risen since the death of his mother last autumn. Polling released this week found the King’s positive ratings were rising, with 62 per cent believing that Charles will be good for the monarchy.

The results are in stark contrast to a poll in March last year, when 39 per cent of people predicted he would be a good king. Thirty-one per cent believed he would be a bad king, compared with 20 per cent in the latest poll.

Graeme Burnham, a 72-year-old Victorian cattle farmer, was one of those Geelong Grammar students who still fondly recalls those school days with a young prince. He is also convinced Charles will be a good king.

“There was absolutely no pomp and ceremony. There was no bullshit,” he said recently.

“He’s a thoroughly decent bloke,” Burnham said. “He’s done the hard yards. He absolutely deserves a really good go.”

Get a note directly from our foreign correspondents on what’s making headlines around the world. Sign up for the weekly What in the World newsletter here.

Most Viewed in World

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article